Economic Impact Is Across the Board

The implications here are enormous. Like the switch to a low-carbon future, the dollars that are affected by Obamacare filter throughout the economy, affecting jobs, personal savings, anywhere that dollars are spent.

This does not go double for convicts, addicts and mental health patients in a strict sense of the word, but the impacts are certainly concentrated and harder felt by those who are the most marginalized. A repeal will certainly “erase the progress we’ve made and hit working families the hardest,” said Congressman Deutch. But those with the greatest need or at the greatest risk will certainly feel the impact all the more.

A few alarming examples stand out among individual states. In Maine, for example, the rate of overdose fatalities rose by 13.6 percent from 2015 to 2016, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Headlines now say the repeal will leave 8,300 addicts without health insurance, despite the stark reality that the state faces with over one overdose fatality per day. During the first nine-month of 2016, a total of 286 deaths from overdoses were recorded, according to the state’s Office of the Attorneys General.

Researchers at Harvard and New York University in a widely circulated state by state report in January said that that 19,000 people with mental health disorders and addictions will lose their treatment options in the state of Maine with the repeal of Obamacare. “At a time when drug overdose deaths are at an all time high in Maine, health care advocates say the push by Republicans in Congress to repeal the ACA with no clear replacement will make the problem even worse,” Maine Public reported.

According to the research, 11,000 in Maine receive mental health treatment through the Medicaid expansion plan, while another 8,000 receive services to treat their substance abuse disorder and both groups largely found insurance either unavailable due to their pre-existing conditions or simply unaffordable prior to the ACA, said Dr. Sherry Glied, a Harvard Medical School lecturer who is also a professor of NYU’s Hunter College.

“We have people dying every day, and this will just increase that,” Maine Public quoted Mallory Shaughnessy of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services in Maine as saying.

With numbers equally startling, reports indicate that 80,000 persons across the state of Maine will lose their coverage with an ACA repeal, which will leave many clinics and hospitals high and dry. Some facilities expanded services in the strength of the new provisions and the Maine Hospital Association estimated that the state’s hospitals take in $200 million a year from those covered by Obamacare. Given the point that Maine hospitals generally operate on paper-thin margins – averaging about 1 percent, the association said any rollback is too much. “There just isn’t room for dramatic negative impacts,” said MHA vice president of government affairs Jeffrey Austin.

Across the country, Gov. Jerry Brown of California is also issuing dire warnings as to the effect of an ACA repeal, warning members of Congress that a shift in responsibility to the states would be disastrous. “I implore you: Don’t just shift billions of dollars of costs to the state. That would be a very cynical way to prop up the federal budget – and devastating to millions of Americans,” Brown said.

Among the repercussions for California, according to State Senate Leader Kevin de Leon in an early January meeting with reporters, “if in fact the Affordable Care Act is eviscerated,” he said, “we’re talking about potentially 200,000 jobs being lost in California,” he said. “Jobs related to the healthcare industry.”

The plight of communities could not be clearer by looking at the case of Louisville, Kentucky. In a state in which the overdose fatality rate soared 21.1 percent from 2015 to 2016, the rate in Louisville went into hyper-drive, climbing 31 percent in one year.

Caught in the midst of this spike is Rhonda Hardin, age 40, who struggles with heroin addiction and the behaviors that come with it, including an assortment of crimes, like petty theft, required to support her habit.

Her struggle is daily, but with the help of a monthly shot of Vivitrol, her cravings can be controlled. Her nurse manager Beth McGill explains that this works “like a manhole cover” to block the pleasure she would have otherwise gotten with a hit of heroin. No pleasure – what’s the point of shooting up?

The drug, which is administered with counseling, comes at a steep price and Hardin admits that the battle to combat her cravings would quickly be lost without the Medicaid expansion program that covers the Vivitrol shot that cost $1,000 per injection. On her own, she says, “It’s easier to get $20 or $40 than it is to get $1,000,” noting she would soon give in to her addiction if she had $40 in her pocket and had weeks to go to save another $940 for a shot of Vivitrol.

New Treatments Threatened

With more and more addiction treatment strategies relying on expensive medications, the days of staring down at addiction through 12-Step programs less certain than they used to be, but it is not only medication that is expensive. Twenty-eight day stays in a rehabilitation clinic are also expensive, as is out-patient care and individual hours in therapy. Still, there’s no denying the trend towards pharmaceutical relief for addictions, seen in the growing list of compounds used to block cravings or replace riskier drug taking with medically-advised options. Besides Vivitrol, there’s Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Naltrexone, each with a variety of brand names, some of which are simply variations on the theme, such as Zubsolv, which is a combination of Buprenorphine and Naloxone.

Back in Louisville, Vice News reporter Dexter Thomas made his way into the local jail to ask the simple question how many the cell block that includes Hardin are addicted to opioids. In a group gesture, everyone in view – about 15 or so women – raise their hands. “That’s all of you,” the reporter says.

But thanks to Obamacare, the game plan has changed dramatically. Lock up in many locations means throw away the key for a while, but now, says the assistant director of Louisville Metro Corrections Steve Durham, two questions are asked of everyone who is processed by the city’s department of corrections, a number that reached 32,000 last year. Those two questions: Do you have health insurance and do you want health insurance,” Durham said.

Prior to that, a release from jail was similar to going to jail, in that they both entailed being neglected on one of two sides of a set of bars. In days prior to Obamacare, a release from prison meant opening the doors and saying “good-bye,” said Durham. Now, it involves connecting with a health care program to help an addict manage what comes next.

That brings us to the coldest statistic of all to come out of the ACA repeal debate, which is haunting many Republican politicians, who still seem duty bound to repeal a law that has helped millions of people.

The number, appeared in a mid-January op-ed piece published in The Washington Post and The Chicago Tribune. The Tribune was succinct: “Repealing Obamacare will kill more than 43,000 people a year,” the headline read.

Things had gotten politically cold, but now it was very, very cold – a January headline with frigid temperatures outside and a sense of doom in black and white. The number, to put it into perspective, would be more than twice the number of U.S. casualties in the height of the Vietnam war – in 1968, when 16,899 U.S. soldiers died in Vietnam, a figure well above the two years bracketing that, 1967 and 1969, when fewer than 12,000 U.S. soldiers died in that widely unpopular conflict.

The number 43,000 would, in fact, put the repeal of Obamacare right above suicide as one of the country’s leading causes of death, the number of self-inflicted deaths being listed in 2014 by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention at 42,773.

Data Can Be Confusing

Numbers, of course, can be deceiving, depending on who is doing the spinning. The number 43,956 deaths each year comes from two University of New York professors of public health David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler, who both lecturers at Harvard Medical School and co-founders of the Physicians for a National Health Program. In their op-ed piece, the authors get right to the point, noting “the first problem is that Republicans don’t have a clear replacement plan,” for Obamacare, despite years of huffing and puffing about what they see as a seriously costly and cumbersome program.

The educators also note that numbers that come out of the mouths of politicians can be misleading, but that even the vague hints of a replacement plan from the Republican Party come up far short in terms of coverage compared to the current system. “Much of what they – notably House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., and Rep. Tom Price, R-Ga., who is Trump’s nominee to head the Department of Health and Human Services, which will be in charge of dismantling the ACA – have advocated in place of the ACA would hollow out the coverage of many who were unaffected by the law, harming them and probably raising their death rates,” the professors wrote.

However, “The story is in the data,” says Himmelstein and Woolhandler. Or, more accurately, it is about data in reverse, since the number comes from a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine that found that when Medicaid coverage is expanded, four every 455 people who picked up coverage with the expansion, one life was saved.

That figure held true when the study included new coverage across several states. In reverse, “Applying that figure to an even conservative estimate of 20 million losing coverage in the event of an ACA repeal yields an estimate of 43,956 deaths annually.”

Since numbers like this scare everybody, even politicians in buttoned up suits, the authors went on to explain that the reaction to a headline calling attention to close to 45,000 preventable deaths per year was met with a flurry of responses on both sides of the aisle in Washington. The chief responses came from Senator Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., who was awarded “four Pinocchios” from Glenn Kessler of The Washington Post for merely asserting that 36,000 people would die each year with a repeal of Obamacare.

This was countered by fresh responses from conservatives, including Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institute, a conservative think-tank, who estimated that a Republican replacement plan would certainly reduce the repeal’s death toll, while Grover Norquist, a conservative pundit, noted that the tax cuts that a repeal would generate “would be a massive boon for the middle class.”

While each of those responses might sound more cynical than the next, the award goes to Aaron for suggesting all would be not as catastrophic as the headlines read simply because of the Republican replacement plant, which doesn’t exist.

This puts a new spin on the adage that the only thing you can count on in life is death and taxes, except this is that adage turned upside down. In this case, tax relief for the wealthy gained through a repeal of a health insurance law for the working class and poor could be said to prompt an increase in the death rate for those at the bottom of the social strata.

Of course, anyone whose life comes in contact with the addiction recovery community – addicts, jailers, counselors, judges, husbands, wives, sisters, mothers, fathers, brothers, aunts and uncles – already knows the answer to who gets hurt when benefits are rolled back.

The unsung story of an Obamacare repeal lies in the class warfare that underscores the legislation, because the country already had an insurance program for the poorest citizens in Medicaid and Obamacare was never billed as a replacement for that, although it included a Medicaid expansion package to reach out further to the country’s flailing lower-middle class, who had just come through the worst economic slowdown in the nation’s history after the Great Depression.

This, of course, is when the highly regarded television series “Breaking Bad,” came into its own, propelling actor Bryan Cranston to stardom for his portrayal of high school chemistry teacher Walter White, who turned to making the illegal drug methamphetamine to keep his family finances from going down the tubes after he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

It is safe to say that “Breaking Bad” was a story of its time and that time – the series ran from September 2008 through the 2013 season – coincided aptly and not coincidentally with the advent of the ACA law. The nation, in effect, could relate to a mild mannered high school teacher going off the deep end after discovering that his health insurance plan was insufficient for his needs and would have bankrupt his innocent family.

While the country facing the same dilemma and lagging behind much of the rest of the world in health care options, the Opioid addiction epidemic struck. Overdose deaths skyrocketed in nearly every state with various communities ravaged by spikes in heroin and prescription drug use. Opioid drugs – prescription and otherwise – are the primary culprits behind the 33,091 drug overdose fatalities in the country in 2015 – a number that is four times what it was in 1999, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, the agency says, drug overdose fatalities reached higher than 28 deaths per 100,000 in five states: Rhode Island with a rate of 28.2 per 100,000, Ohio and Kentucky (29.9 per 100,000), New Hampshire (34.3 per 100,000) and West Virginia with an astonishing rate of 41.5 deaths per 100,000 residents.

While some communities saw enormous spikes in drug overdosing, the main increases were seen in the Northeast and South Census districts, with some states showing especially significant increases. From 2014 to 2015, overdose fatalities jumped 25.6 percent in Connecticut, 22.7 percent in Florida and 35.3 percent in Massachusetts. In New Jersey, the spike was 16.4 percent; in Ohio 21.5 percent. The list goes on and on: A 30.9 percent jump in New Hampshire, a 20.1 percent jump in Pennsylvania. In New York, fatalities jumped 20.4 percent year to year.

More alarming, a few states were listed as having significant increases two years running. Maine was one, up 26.2 percent in 2014 to 2015 after landing on the significant jump list the previous year. New Hampshire has seen back to back spikes, as has Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee and Rhode Island.

Of course, newspapers, especially local ones, didn’t need a repeal of Obamacare for these numbers to make headlines.

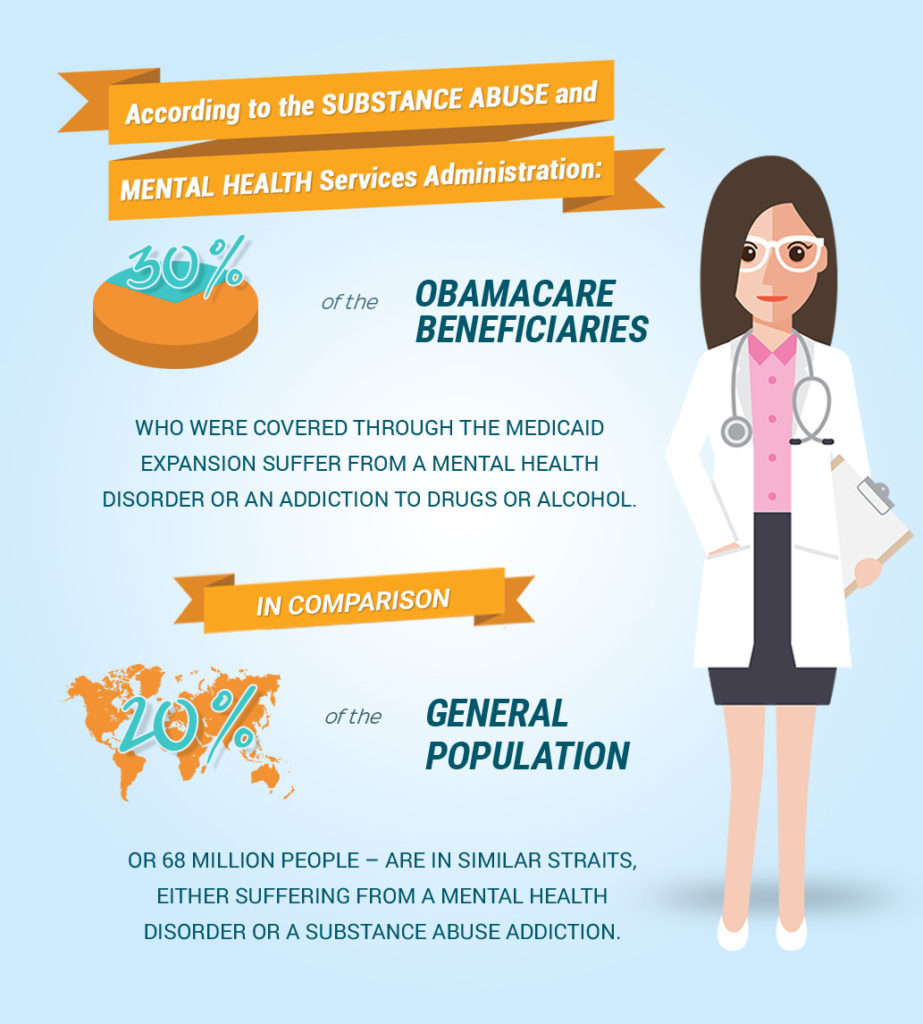

A repeal of Obamacare is described as nothing short of pouring gasoline on the fire. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 30 percent of the Obamacare beneficiaries who were covered through the Medicaid expansion suffer from a mental health disorder or an addiction to drugs or alcohol. In comparison, says the American Psychiatric Association, as reported by USA Today, 20 percent of the general population – or 68 million people – are in similar straits, either suffering from a mental health disorder or a substance abuse addiction.

This doesn’t bode well for the section of society hit by addictions in one form or another and fear could not be running higher. Are we headed back to a “Breaking Bad” scenario? In real life, this tends to mean addiction first, diagnosis later, as opposed to the television version in which diagnosis comes before the turn to drugs and crime.